March 24, 2016

By Dr. James C. Kroll

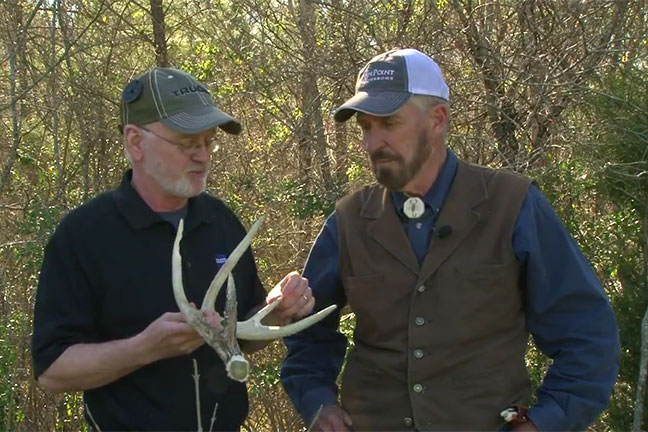

While most whitetail hunters think of "patterning" as something done just before and during deer season, it's really a year-round process. That includes using information from antler casting (shedding) to gain a better understanding of the herd.

Knowing when and where bucks cast their antlers this winter can tell you a great deal about what they might do next season.

At our Institute for White-tailed Deer Management & Research, we've studied the antler cycle for almost four decades now, and in a multitude of geographic locations. As part of this, we've monitored when and where antlers are cast.

Advertisement

Our research clearly shows that unless something about your hunting territory drastically changes, bucks will cast at generally the same times and in roughly the same places (within a few hundred yards) each year. Of course, where a buck is at the end of the antler cycle might be miles from your fall hunting area. This is where trail cameras can come into play.

Many deer hunters have one or two cameras, and they start using them just prior to the season to find potential targets. But the images can tell you much more about overall deer patterns and the lives of individual bucks.

Antlers are like fingerprints: Each set has unique characteristics that can be used to identify a specific buck.

Advertisement

By using trail cameras in our hunting areas 365 days a year, we can determine when certain bucks show up and when they leave. If you have a photo or video of a specific buck, it should be simple to tie him to his cast antlers. This can tell you whether he's a resident or a "floater" that probably will leave your property later in the season.

Comparing information on cast antlers with your neighbors, as many private-land managers now do, can provide a wealth of information about where various bucks are spending different times of year.

Antler Intel

I hear a lot of misinformation about what dropped antlers can tell you. The most common belief is that you can age a buck by examining the profile of the area where the antler was attached to the pedicel of the skull. Many hunters think that if the base of the antler (area beneath the burr) is convex, the deer is old.

But we've never seen a consistent link between that and a buck's age. It's just normal variation in antler architecture. So what can you can learn from a cast antler? Quite a bit, actually.

For instance, there's a clear relationship between age and certain antler metrics. Basal circumference and beam length are especially good indicators of age. Those measurements often are taken by wildlife agency biologists collecting harvest data.

Many states have adopted antler restrictions (which for the most part, have been very popular among hunters). The two most commonly used restrictions are: (1) number of antler points; and (2) antler spread.

If the goal is to protect yearling bucks from harvest, number of points has very little to do with age; even some yearlings have 6-8 points. However, focusing on spread can protect a large percentage of yearlings. In most areas, a minimum of 15 inches of outside spread will suffice. (Outside spread is much easier than inside spread for a hunter to gauge under field conditions.)

One of the criticisms of going by minimum spread is that mature bucks with narrow racks are falsely protected by such regulations. That's why, for private deer management in areas with no legal minimum spread, we add as an alternative a minimum beam length of 18 inches. Most bucks will achieve a beam of that length by 3 1/2 years of age, regardless of antler spread.

So measure the cast antlers you collect this year, collecting the following data: basal circumference, beam length, number of points and the standard additional Boone & Crockett measurements. You then can develop a picture of the age structure of your buck herd.

Nutrition Clues

Antlers are primarily composed of protein, calcium and phosphorus, plus micronutrients such as selenium, zinc and copper. A brief examination of cast antlers can tell you much about the nutritional plane of your herd.

First, take a look at the basal third of the antler beam, starting at the burr (attachment to the pedicel). The small, bead-like structures that form in rows up the antler beam are used like a rasp to make rubs. These bumps are called "pearls" by scientists.

The abundance and prominence of pearls is a sure indicator of nutrition. If they're absent or faint, the buck probably had a nutrition problem during antler development. This knowledge can help you modify your nutrition efforts (supplemental feeding, food plots and/or native forage) as needed.

Whose Buck Is It?

Obviously, not all of the bucks casting antlers on your property will have spent the growing season there. Nor will all of "your" bucks leave their antlers on your land after the season. Compare all antlers you collect each year to assess the uniformity of antler appearance.

Having some with pearls and others without tells you the bucks ending up on your property probably come from more than one other local property. Determining which ones come from another property is problematic, unless you return to your trail camera photos for identification.

Beginning some years ago, research associate Ben Koerth and I conducted a landmark study on antler growth in free-range whitetails. Operating under a research permit, for more than 15 years we used helicopter net guns to capture yearling bucks and buck fawns. We then marked them with year-coded and numbered ear tags and released them back into the wild.

In subsequent years we recaptured many of the bucks or had their measurements and photos returned to us by successful hunters. After capturing thousands of wild bucks and looking at how their antlers developed year to year, we concluded there's absolutely no relationship between the first set of antlers and what a buck ultimately grows as a mature individual. Even so, an examination of yearling bucks can tell you a great deal about your herd.

Cast antler hunters tend to focus on the bigger ones, rather than searching hard for all antlers dropped in a specific area. There are more bragging rights with big ones, I suppose. Yet we all can learn far more from the cast antlers of young bucks than from those of mature deer.

Collect antlers obviously off yearling bucks and then arrange them by size. While an 8-point yearling rack doesn't mean a buck will become a monster, it does tell you something about the time of year at which he was born. If you have a broad distribution in yearling antler size, with many of them being spikes, you probably have a breeding issue within your herd. An extended rut causes some fawns to be born late, resulting in smaller antlers as their first sets at age 1 1/2.

A "trickle" rut stems from a host of factors, but usually poor nutrition and skewed sex ratios. In well-managed herds, the rut should occur over only a few days, resulting some 195 days later in a distinct peak of fawning. This peak is timed to the best growing conditions and should result in very few spikes.

Another important thing you can learn from cast antlers comes from determining the percentage of antlers with broken tines or beams. This is a clear indication of the amount of fighting going on in that antler cycle. As the buck:doe ratio approaches 1:1, the amount of fighting and resulting antler damage increase. Conversely, a pile of pristine antlers, when combined with your yearling antler information, suggests a possible sex ratio problem.

Lastly, examine your antlers for signs of rodent gnawing — especially those you pick up just after the breeding season ends. In areas with calcium and/or phosphorus deficiencies, antlers are attacked by squirrels and other rodents almost as soon as they hit the ground. Conversely, those lying in rodent-laden areas for a year or more without being gnawed suggest adequate mineral nutrition.

In Conclusion

Studying cast antlers might not tell you all you'd like to know about the bucks that dropped them, but it can offer key information and help you solve the patterning puzzle. Form cooperative relationships with neighbors to learn as much as you can about not only your own land but also deer throughout the broader geographic area around it. "Shed season" is a great time to do just that.